US GDP growth is still too strong

The GDP report for the first quarter of 2022 came out last week. The common reaction to the report was negative, as most focused on the -1.4% yearly pace decline in estimated real GDP. I will argue, from the standpoint of seeking economic stability, and conditional on the information we had before the report, that the report was in fact a moderately positive release.

Background

Let’s review some facts and assumptions I make, before digging into the argument. Firstly, when we hear “GDP” in the media, we are almost certainly hearing them reference real GDP figures. Real GDP is the amount of spending on finished goods and services in a geographical area, typically within a single quarter or year, divided by a special GDP deflator index, which maps that nominal spending, into an inflation-controlled amount.

Real GDP is absolutely a conceptually useful timeseries, but we should understand that it’s really a statistical construct, not a direct measurement of reality. Nominal GDP, on the other hand, is a direct measurement of reality, it corresponds to the actual amount of currency spent on final goods and services, within a certain geographical area, within a certain period of time.

Generally speaking, nominal GDP is the more important series, a fact which the economics profession is gradually coming to realize, thanks to the efforts of Professor Scott Sumner. Nominal GDP is more important, because modern economies are characterized by price stickiness. Economic actors can’t quickly adjust prices and contracts to optimize production given the current or expected rate of spending-flow. Instead, the central bank has to, or at least should try to manage the value of the currency such that the flow of spending through the economy optimizes, or at least doesn’t disastrously hinder production of goods and services.

In practice, in a large and diversified consumer-focused economy like the USA, this means that monetary authorities implicitly seek to stabilize nominal GDP around a 4 or 5% trendline. This allows for about 2% inflation and about 2% real growth. Let’s leave it there, for more details, start with the Market Monetarism Wiki entry.

The Report

The US economy faces two big issues today:

Substantial backlogs of many industrial goods, resulting from several months of low production due to the corona virus panic of 2020.

A shift in the composition of final spending from non-retail spending, into retail spending. We see this in the Retail and Food Service Sales series I’ve posted on recently.

We could consider that there’s also a third problem, namely that nominal GDP has recovered too strongly, and is now above a reasonable 4.5% target trendline, extrapolated from Q4 of 2019. However, as the chart below shows, GDP is only trivially above my proposed 4.5% target path, starting in Q4 of 2019. Importantly, and this is why I was moderately encouraged by the report, the quarter-on-quarterly growth rate in nominal GDP dropped from an annualized and absolutely scorching and unsustainable pace of 14.5% (!!!!) in Q4 of 2021, to a merely reckless (if sustained) yearly pace of 6.5% in Q1 of 2022.

(Note Q2 and Q3 of 2020 get cut off by the narrow y-axis range, the point is not to focus on those outlier quarters)

I say the 14.5% and 6.5% figures are “scorching” and “reckless” only in the sense that they would be so if sustained for quarters or years into the future. When we got that 14.5% annualized growth at the end of 2021, it was basically just what we needed, a final surge in spending to get NGDP back to the trend line.

I would argue the Fed should have begun tightening in summer 2021, and indeed I was sure they would and wrote as much. It’d have been preferable to approach the target trendline a little more gradually. Instead the Fed overdid it a little, allowed NGDP expectations to rise up to…say 5.5% or 6% per year. We can’t directly see NGDP expectations, but certainly they are coming back to earth now, reflected in declining equity prices. The Russian Special Military Operation in the Ukraine of course is affecting commodity prices, but I suspect part of the reason commodity prices aren’t even higher is that the US economy is expected to slow. Copper prices, which are a strong predictor of near-term global growth, and not dominated by Russian production, are at least down sharply in the last two weeks, mirroring equities. When you have 6.5% annualized nominal GDP growth and high inflation, slowing is a good thing.

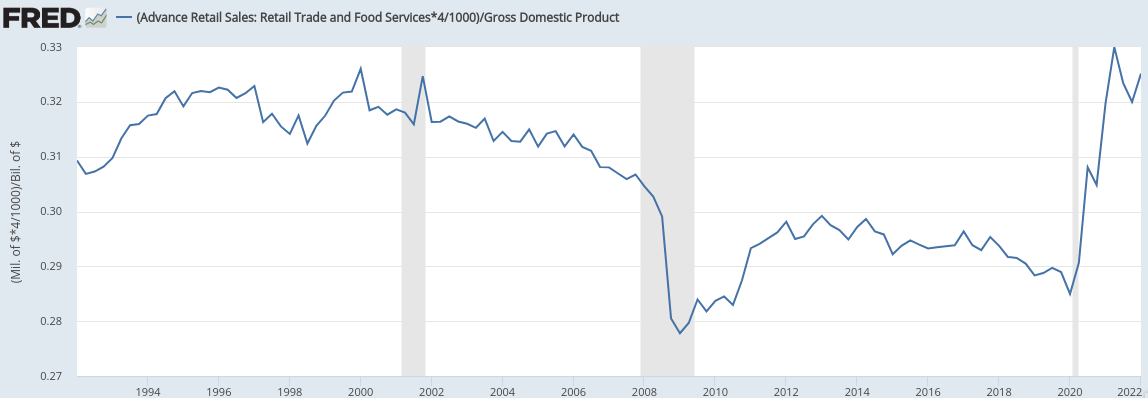

A note on retail sales: in my last post I claimed the Fed was overstimulating the economy based on the breakout trend in retail sales. I probably made too strong of a case there, and instead should have focused on the explosion in retail spending, as an explanation for consumer price inflation. When we express retail and food services sales as a percentage of GDP, we see that retail spending has increased from about 29% of pre-coof GDP, to about 32%. It’s for the best that the Fed on concern itself too much which copositional shifts in GDP like this, and instead focus on steady growth in total spending. Still, it helps explain why inflation has been so hot despite nearly optimal NGDP management, spending is shifting from other GDP components, into retail, which disproportionately affects the CPI and PCE indices.

Inflation will indeed prove “transitory” as either the ratio of retail to GDP comes back to a more normal level, or the relative prices of retail goods rise toward the equilibrium necessary to sustain an economy 32.5% dedicated to retail, rather than 29% dedicated. 3% of US GDP is no joke.

Conclusion

There’s nothing the Fed can do about supply bottlenecks, the student loan moratorium that jarringly stimulated retail sales, the embargo on Russia or the…bizarre series of mishaps that have apparently befallen the agricultural sector. All they can do, all they should do, is work to deliver steady, predictable nominal GDP growth. They’ve done that, the Fed got us back to trend nominal GDP; now they need to make sure they correctly steward expectations so that we don’t blow past that trendline into a disastrous inflation situation.

The latest GDP report was seen as bad news as high inflation in the GDP deflator yielded a bad real GDP number. The report is however good news, because it shows the pace of nominal GDP is slowing rapidly, from 14.5% to 6.5%. When combined with strong drops in equity markets and copper prices, this suggested US nominal GDP growth will continue to slow.

If we can get nominal GDP in the sweet spot of an between 4% and 5% annualized in the coming quarters, the Fed will have pulled off the fabled “soft landing”, regardless of what the real GDP figures report. Real GDP may fall, we may have permanently damaged the supply side of the economy with all the madness of the last 3 years, but as long as nominal GDP is properly managed, we needn’t have a true recession, with punishing job losses, and underutilized economic potential.